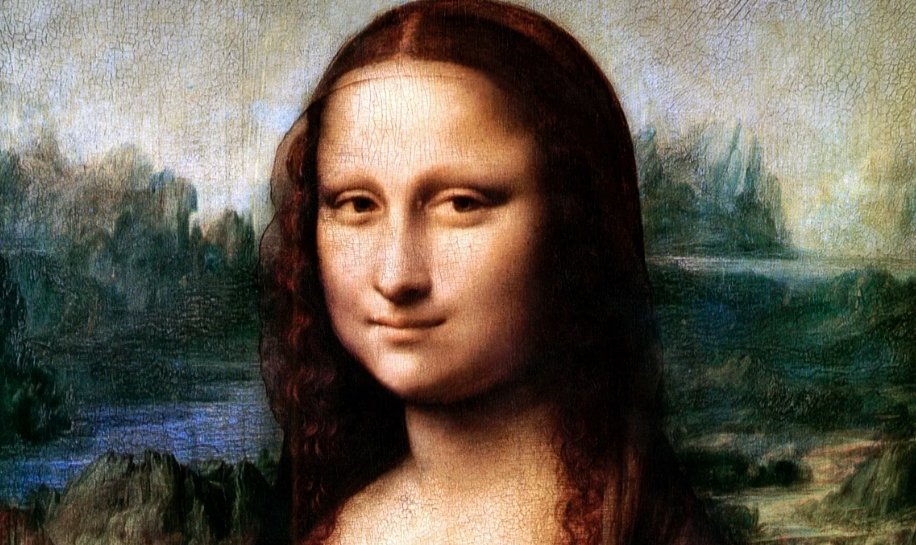

FREIBURG, Germany — After more than 500 years of debate, speculation, and scrutiny, scientists say they’ve settled the most enduring question in Western art: Is the Mona Lisa smiling? The answer, according to a new peer-reviewed study, is yes.

A team of researchers from the Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health in Freiburg has concluded that the Mona Lisa’s enigmatic expression is indeed one of happiness, not melancholy — despite long-held assumptions among art historians and critics that she was frowning.

Their findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, not only challenge centuries of interpretation but also underscore the subjective and fluid nature of visual perception.

“We were very surprised to find out that the original Mona Lisa is almost always seen as being happy,” said Jürgen Kornmeier, lead author of the study. “That calls the common opinion among art historians into question.”

A Face of Many Moods

The researchers conducted two experiments using digital manipulations of the painting. They created eight modified versions of the Mona Lisa’s face — some with subtle enhancements to make her appear happier, others slightly sadder. These, along with the unaltered original, were randomized and presented to participants in quick succession, approximately 30 times each.

The goal was to assess how viewers interpreted each facial expression — and where the original version fell on that emotional spectrum.

According to the researchers, the original Mona Lisa was identified as “smiling” 100% of the time by participants, placing it firmly in the happy category.

Context Is Everything

To further probe the mechanics of visual emotion recognition, the scientists ran a second trial. This time, the original painting was the only smiling version, while the others depicted varying degrees of sadness.

Interestingly, participants began to interpret the original Mona Lisa as more somber when placed in this new context — an effect the team says highlights how perception is dynamically shaped by surrounding stimuli.

“The data show that our perception, for instance of whether something is sad or happy, is not absolute but adapts to the environment with astonishing speed,” Kornmeier noted.

Science Meets Art History

The findings challenge a long tradition of art criticism that has framed the Mona Lisa’s expression as cryptic, sorrowful, or emotionally ambiguous. Some historians have linked her perceived melancholy to personal tragedy, illness, or even da Vinci’s own reflective nature.

But the new data suggest that much of this ambiguity might be projected by the viewer rather than embedded in the painting itself.

“Our brain tries to interpret what we see,” the researchers wrote. “But even when we believe we’re seeing something objectively, it’s being filtered through past experiences and contextual cues.”

The Woman Behind the Smile

The subject of the painting, Lisa Gherardini, was a Florentine woman believed to have lived a modestly comfortable life. Married to cloth merchant Francesco del Giocondo, she raised their children after his death — reportedly supported by his modest wealth.

Leonardo da Vinci painted her portrait around 1503, and the work remained relatively obscure until it became an icon of Renaissance art in the 19th century — especially after being stolen from the Louvre in 1911, which launched it to global fame.

Since then, the painting’s subtle smile has inspired countless poems, films, parodies, and psychological theories. Sigmund Freud believed it revealed da Vinci’s repressed maternal memories. Others interpreted it as evidence of illness, pregnancy, or even a toothache.

But if the Freiburg study is correct, Mona Lisa was simply… smiling.