Experts have confirmed that bones hidden in a wall at the Church of St Mary and St Eanswythe in Folkestone, England, belong to Saint Eanswythe, a seventh century princess and one of the earliest English saints. This discovery, verified through new analysis in 2025, sheds light on early Christian history in Britain and marks a major find after the remains sat unexamined for over a century.

Discovery Sparks New Interest

Workers first uncovered the bones in 1885 during repairs at the church in Folkestone, a coastal town in Kent. They found them sealed in a lead container behind a wall, but no one could prove whose they were at the time.

Local legends tied the remains to Saint Eanswythe, the church’s namesake, yet proper testing waited until recent years. The bones stayed in place due to their religious value, with rules against removing them from the site.

In 2020, initial studies suggested a link to the saint, but full confirmation came only now. This timing aligns with growing public fascination in Anglo Saxon history, boosted by shows like The Last Kingdom and museum exhibits on early Britain.

Archaeologists note that hiding relics was common during turbulent times, protecting them from harm. This case fits that pattern, adding to the excitement around the find.

Who Was This Early Saint?

Saint Eanswythe lived during a key era when Christianity spread across England. Born around 614 AD, she was the granddaughter of King Ethelbert, the first Christian ruler in Kent.

Her father, King Eadbald, built a monastery in Folkestone, which became one of the first for women in the country. Eanswythe joined as a teenager and later led it as abbess.

Historians believe she performed miracles, like creating a water source that flowed uphill, earning her local fame. She died young, likely in her late teens or early twenties, between 640 and 650 AD.

Her life reflects the shift from pagan to Christian ways in seventh century Britain. Family ties to Frankish royalty also highlight cross channel influences during that period.

- Founded England’s first nunnery around 630 AD

- Known for charity work and healing the sick

- Venerated as Folkestone’s patron saint for centuries

How Science Proved the Identity

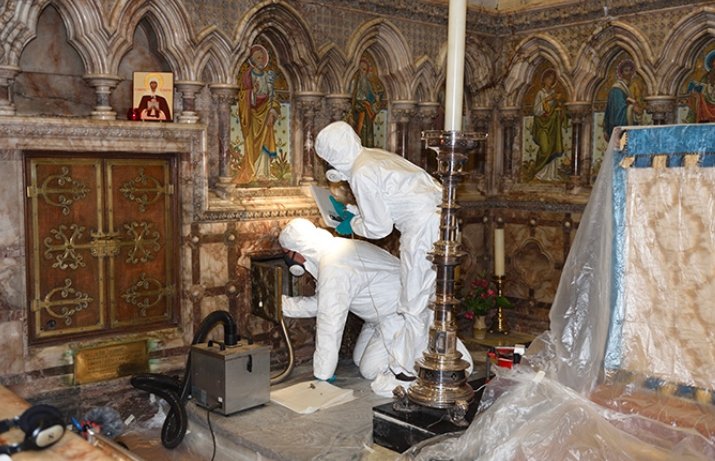

Recent tests used advanced methods to date and analyze the bones without moving them far. Experts from Canterbury Christ Church University and other groups led the effort.

Carbon dating placed the remains in the mid seventh century, matching Eanswythe’s lifespan. Dental analysis showed the person was a young woman, fitting historical records.

Bone structure indicated a diet rich in fish, common for coastal Kent at the time. This detail strengthened the case, as Eanswythe lived by the sea.

The team faced limits, working only inside the church to respect traditions. They used portable tools for scans and samples, ensuring minimal disturbance.

This confirmation builds on 2020 findings but adds DNA insights, ruling out other possibilities. It stands as a rare example of verified saint relics in England.

Why This Matters for History

The find offers a direct link to Anglo Saxon times, a period with few surviving artifacts. Most relics were lost during the Reformation in the 1500s, when many were destroyed or hidden.

Eanswythe’s bones are now the oldest confirmed saint remains in England, beating others by centuries. This boosts Folkestone’s profile as a historical site.

Experts say it could draw tourists and scholars, much like recent digs at Sutton Hoo, which revealed ship burials from the same era. Ties to King Ethelbert connect it to Canterbury Cathedral’s story.

On a broader scale, it highlights women’s roles in early Christianity. Eanswythe led a community when few women held power, inspiring modern discussions on gender in history.

| Key Historical Ties | Details |

|---|---|

| Family Line | Granddaughter of King Ethelbert, first Christian king of Kent |

| Monastery Role | Abbess of Folkestone’s first women’s monastery |

| Era Significance | Lived during Christianity’s rise in England, 600s AD |

| Modern Impact | Boosts local tourism and educational programs |

Preservation Efforts and Next Steps

After confirmation, the bones returned to a special reliquary in the church. This setup allows public viewing while keeping them safe.

Church leaders plan events to share the story, including talks and exhibits. A 2024 ceremony marked their rehousing, drawing crowds from across Britain.

Looking ahead, more studies might explore DNA links to other royal lines. This could reveal migration patterns in early medieval Europe.

The discovery ties into 2025 trends, like renewed interest in heritage amid global events. It reminds people of shared roots in uncertain times.

Public Reaction and Ongoing Buzz

News of the confirmation spread quickly on social media, with posts praising the blend of science and faith. Historians and locals alike celebrated the find.

Some compare it to other 2025 discoveries, such as ancient Roman artifacts in London. This keeps early British history in the spotlight.

For visitors, the church now offers guided tours, making history accessible. It solves questions about Eanswythe’s fate and entertains with tales of miracles.

Share your thoughts on this fascinating discovery in the comments below, or pass the article to friends interested in history. What other ancient mysteries would you like explored?