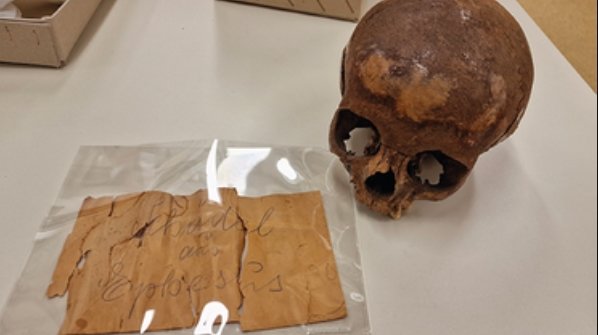

For nearly a century, historians and archaeologists believed that a skull discovered in the ancient city of Ephesus in 1929 belonged to Cleopatra’s half-sister, Arsinoë IV. The remains were found in a grand mausoleum known as the “Octagon,” and historical accounts suggested that Arsinoë, who was executed in Ephesus in 41 BCE, was buried there. However, a recent study using cutting-edge technology has overturned this long-held assumption, revealing that the skull actually belonged to an 11- to 14-year-old boy.

The discovery has raised new questions about the identity of the young boy and the circumstances surrounding his burial in such an elaborate tomb. Researchers are now left with the mystery of where Arsinoë’s remains might be and why the boy was buried in such an important location.

The Discovery of the Skull in Ephesus

The skull was unearthed in 1929 by Austrian archaeologist Josef Keil, who was excavating the Octagon, an elaborate mausoleum in the ancient city of Ephesus, located in modern-day Turkey. The sarcophagus containing the skull was waterlogged, and the discovery of the skull without any grave goods or inscriptions left researchers speculating about its owner. Historical records had suggested that Arsinoë IV, Cleopatra’s half-sister, may have been buried there after her execution in 41 BCE.

Arsinoë IV was known for her resistance against Cleopatra and Julius Caesar during the Siege of Alexandria. After her defeat, she was exiled to Ephesus, where she met her untimely death under the orders of Mark Antony. In 1982, further excavations at the site uncovered additional remains, further fueling the theory that the tomb belonged to Arsinoë.

However, new analysis of the remains has raised doubts about this identification.

The Young Boy Behind the Ephesus Skull

In a groundbreaking study published in Scientific Reports, researchers from the University of Vienna and the Austrian Academy of Sciences used advanced technologies to analyze the skull. They discovered several unexpected characteristics, including a severely underdeveloped jawbone (maxilla) and unusual wear patterns on the teeth. The skull also exhibited premature fusion of cranial sutures—bone joints that typically remain open until a person reaches 65 or older. This asymmetry suggested possible health conditions such as a vitamin D deficiency or a genetic disorder.

Radiocarbon dating placed the boy’s death between 205 BCE and 36 BCE, coinciding with the period when Arsinoë lived. However, DNA analysis revealed a crucial detail: the presence of a Y chromosome, indicating that the skull belonged to a male, not a female.

Further testing determined that the skull belonged to a young boy, aged between 11 and 14 at the time of death, completely ruling out the possibility that it was Arsinoë IV.

The Mystery of the Boy’s Identity

While the analysis has definitively proven that the skull does not belong to Arsinoë, researchers are still uncertain about the identity of the young boy. The fact that he was buried in such a significant tomb raises further questions. It’s possible that he came from a wealthy or high-status family, though this remains speculative.

The Octagon mausoleum is an extraordinary site, and the boy’s burial in such a prestigious location suggests he may have been an important figure, though the exact circumstances of his life and death remain unknown.

What Comes Next?

With the identity of the boy still a mystery, scientists are turning their attention to the search for Arsinoë IV’s remains. Despite the new findings, the belief that she was buried in Ephesus persists, and the quest to locate her remains continues.

“We can now say with certainty,” stated Gerhard Weber, the lead author of the study, “that the person buried in the Octagon was not Arsinoë IV, and the search for her remains should continue.”