Recent archaeological discoveries in Portugal have revealed disturbing evidence of cat skinning practices during the medieval period. Excavations along Rua do Registo Civil in Almada unearthed two storage pits containing over 200 cat bone pieces, indicating that domestic cats were skinned for their pelts. This finding sheds light on the treatment of cats in medieval Europe and raises questions about the cultural and economic factors driving this practice.

Archaeological Findings

The discovery of cat bones in Almada has provided the first archaeological evidence of cat skinning in Portugal. Researchers found 202 bone remains belonging to 13 cats, with shallow incisions suggesting they were skinned for their fur. The cuts, located near the snout and above the eyes, indicate a deliberate effort to remove the skin for use as pelts.

The age of the cats varied, with six under four months old, one between five to six months, and six over a year old. This age distribution suggests that the cats were selected for their fur quality, as younger cats would have had softer, more desirable pelts. The presence of these remains among household waste also hints at the less favorable view of cats compared to other animals like dogs, whose remains were not found.

This discovery aligns with similar findings in other parts of Europe, where cat skinning was documented in medieval writings. However, this is the first concrete evidence of the practice in Portugal, providing new insights into medieval European attitudes towards cats and their uses.

Historical Context and Cultural Significance

The practice of skinning cats for their fur was not uncommon in medieval Europe. In addition to Portugal, evidence of cat skinning has been found in Spain, where over 900 cat bones were discovered in pits in El Bordellet. These bones also showed incisions consistent with skinning, indicating a widespread practice across the Iberian Peninsula.

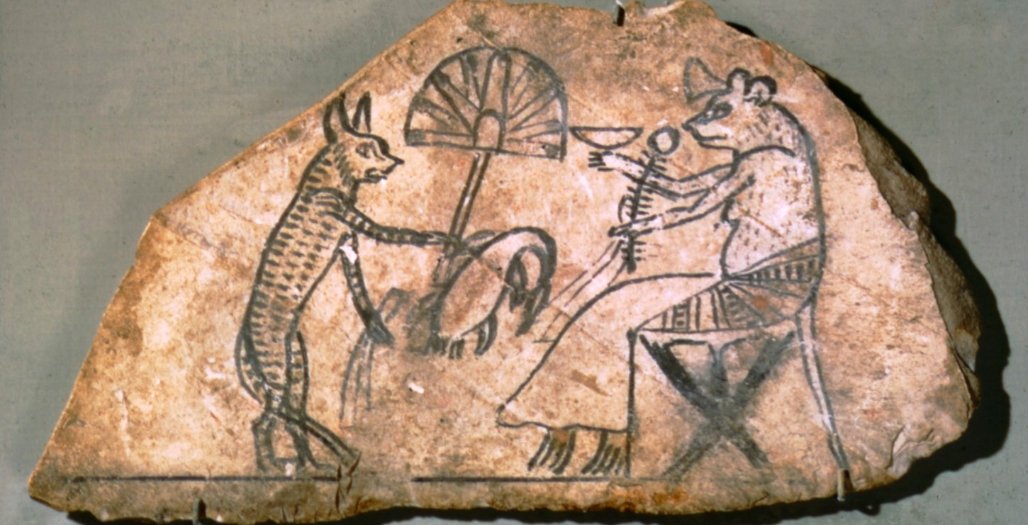

Medieval Europeans valued cat fur for its warmth and softness, making it a sought-after material for clothing and other items. The economic value of cat pelts likely drove the practice, with cats being bred and killed specifically for their fur. This utilitarian view of animals reflects the broader medieval mindset, where animals were often seen primarily as resources.

The findings in Almada also raise questions about the social and cultural attitudes towards cats in medieval Portugal. The presence of cat remains among household waste suggests that cats were not highly valued as companions, unlike dogs. This could indicate a cultural preference for dogs or a utilitarian approach to animals in general.

Implications for Modern Understanding

The discovery of cat skinning practices in medieval Portugal has significant implications for our understanding of medieval European society. It highlights the economic and cultural factors that influenced the treatment of animals and provides a glimpse into the daily lives of medieval people. The findings also challenge modern perceptions of historical animal-human relationships, revealing a more complex and utilitarian approach.

These archaeological discoveries contribute to the broader field of medieval studies, offering new data for researchers to analyze and interpret. They also underscore the importance of continued excavation and study of historical sites, as each new find adds to our knowledge of the past.

The study of medieval cat skinning practices also has relevance for contemporary discussions about animal rights and welfare. By understanding how animals were treated in the past, we can better appreciate the progress made in animal welfare and the ongoing challenges in this field. The findings from Almada serve as a reminder of the need for ethical treatment of animals and the importance of historical context in shaping our views.